Wong Kar-wai’s Blossoms Shanghai drama series offers stock investors painful reality check on past glory

Blossoms Shanghai, Hong Kong filmmaker Wong Kar-wai’s hit about the heady opportunities and possibilities during the early 1990s in China’s financial hub, has captured the collective nostalgia of an entire nation, in more ways than one.

Fans of the wildly popular 30-episode drama have been flocking to the restaurants, bars and clubs featured and visited by the show’s protagonist since its release on December 27. His Huanghe Road neighbourhood, a hub for Shanghai’s Xiao Long Bao (dumplings with a filling of minced pork) and other time-honoured delicacies, is now the must-go destination for out-of-town visitors.

Set in 1992, Blossoms tells the story of A Bao, who struck it rich by punting on the earliest stocks listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, highlighted by a concoction of buying craze, wild price swings and insider trading subplots. At the end, A Bao transformed into Mister Bao as he emerged triumphant against a powerful rival in a stock market showdown.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

At the time of the drama’s setting, Shanghai’s equity market in real life was barely two years old. The all-share Shanghai Composite Index soared 167 per cent that year, on top of 129 per cent in its debut year, according to exchange data. That back-to-back rally was Shanghai’s best two years on record.

“It is all tears and sorrow now, when people like me look back at the stock market,” said Lu Shunxi, a stock punter since trading first began in Shanghai in November 1990. “The birth of China’s stock market gave an opportunity to novice investors who were drawn to a casino-like market to gamble and prosper.”

For a quarter of a century, Shanghai’s stock market rode on China’s economic engine, which roared along at an average of 10 per cent every year from 1994 to 2007. After the 2008 Beijing Olympics, annual growth slowed to an average clip of 7.6 per cent through 2022.

The largest nation of communists also boasted the world’s second-largest capitalist market, valued at US$13 trillion at its peak in December 2021. China was minting dollar billionaires like the fictional A Bao in Blossoms Shanghai at the rate of almost one every day in 2020, before everything came crashing down.

Today, not much resembles the reels in Blossoms Shanghai. China’s legion of 200 million retail investors – double the membership of China’s Communist Party – can be forgiven for hankering for the gravity-defying bygone era. Photo: Weibo/Peter Pau alt=Today, not much resembles the reels in Blossoms Shanghai. China’s legion of 200 million retail investors – double the membership of China’s Communist Party – can be forgiven for hankering for the gravity-defying bygone era. Photo: Weibo/Peter Pau>

China’s government responded to the Covid pandemic in 2020 with quarantines and extreme travel restrictions. Shanghai was locked down for two months in the summer of 2022, when every school, factory, restaurant, shop and office within the city’s limits was ordered to shut. Shanghai’s 25 million residents were mostly kept at home or quarantined at health facilities.

The result was a severe disruption to global supply chains, businesses and livelihoods, from which the economy is still struggling to recover. China’s economy grew at a scant 0.4 per cent in the second quarter of 2022, and only managed to eke out a 5.2 per cent growth in the final quarter of 2033, months after all Covid-19 restrictions were lifted.

Frustrated investors voted with their feet, pulling a record amount of money from the stock market over the past six months, punishing China’s reluctance to deploy a stimulus programme to rescue the economy. Shanghai-listed stocks have lost US$1.45 trillion of value since the market’s peak in December 2021. The nation’s equity market shrank by US$4.2 trillion over the same period, according to market data.

“Trading shares has become my biggest mistake in life since I keep losing money over the past two decades,” said Li Yan, an employee with a state-owned media company in Shanghai. “I have had to deposit more money into my brokerage account to try to overturn the losses. But the attempts have all resulted in more nightmares.”

Li is not alone. Even veterans and hedge fund stars have been brought to their knees in China’s market slump for misreading the tea leaves. Singapore’s hedge fund Asia Genesis Asset Management threw in the towel earlier this month, wrong-footed by its bullish view on Chinese stocks over the past year, as well as its bearish bets on Japanese equities.

Retail investors, shorn of the financial firepower and acumen of institutional fund managers, habitually pin their hopes on government incentives to spark a rally. Beijing has already rolled out a series of market-boosting measures, from stamp-duty cuts to liquidity injection, to put a floor under the plummeting stock prices.

As panic set in this week, China’s top leadership and policymakers – from Premier Li Qiang to central bank governor Pan Gongsheng – stepped in to stem a loss of confidence. The People’s Bank of China said this week that it would return 1 trillion yuan (US$140 billion) to commercial banks on February 5 to spur lending, after surprising the market with a cut in their reserve-requirement ratio.

The Shanghai Stock Exchange has recouped US$330 billion of value, when the market rebounded by almost 3 per cent this week from a five-year low.

“Retail investors have been eagerly awaiting a rally to recover their losses,” said Ivan Li, a fund manager at Loyal Wealth Management in Shanghai. “They want the authorities to show substantial support to the market.”

Many of China’s retail investors want to believe that Blossoms Shanghai is making an oblique reference to a lasting turnaround in the stock market and the economy. The drama has already effectively bolstered retails spending and tourism in Shanghai. It’s a shot in the arm for Gong Zheng, the mayor of Shanghai, after yet another underperforming year of growth.

Some of the world’s biggest money managers, including Fidelity International and Franklin Templeton, are forecasting a rebound in Chinese stocks. More state support will help revive economic growth and confidence, they said, and investors will soon be lured by deeply discounted valuations.

A view of the Shanghai Stock Exchange trading floor on 19 December, 1997. Photo: AFP alt=A view of the Shanghai Stock Exchange trading floor on 19 December, 1997. Photo: AFP>

“The price-to-earnings ratio is standing at a low level,” UBS’ strategist Meng Lei said. “Most investors, without sufficient understanding of the economy, are just not confident that the share prices will rise.”

China opened up its economy in 1978 by giving capitalist forces a greater play in business activities. Shanghai established its stock exchange in November 1990, becoming the first of its kind in the socialist nation. The Shenzhen Stock Exchange was formed in the following month. Beijing did not have one until September 2021.

Today, the Shanghai Stock Exchange is the largest of the three mainland bourses, and home to about 2,300 listed firms with a combined market capitalisation of 44 trillion yuan (US$6.2 trillion), larger than Hong Kong’s US$4.6 trillion market.

Stocks on the Shanghai exchange have gotten cheaper, trading at a price-earnings multiple of 13.4 times future earnings, compared with a five-year average of 14.6 times. The current multiple is 11 times for members of the MSCI China Index, a universe of 700-odd stocks listed at home and abroad.

Market consultant Ying Jianzhong, who played the character of a stock commentator in Blossoms Shanghai, agreed that understanding economic and company fundamentals are indispensable priorities in investing. Confidence among investors, he said, comes from knowing what they buy into.

“In the early days, investors like me had faith in company earnings,” he said in an interview. “We bought bread baked by a listed company we invested in, because we believed that everything we did for the company would help boost its profitability.”

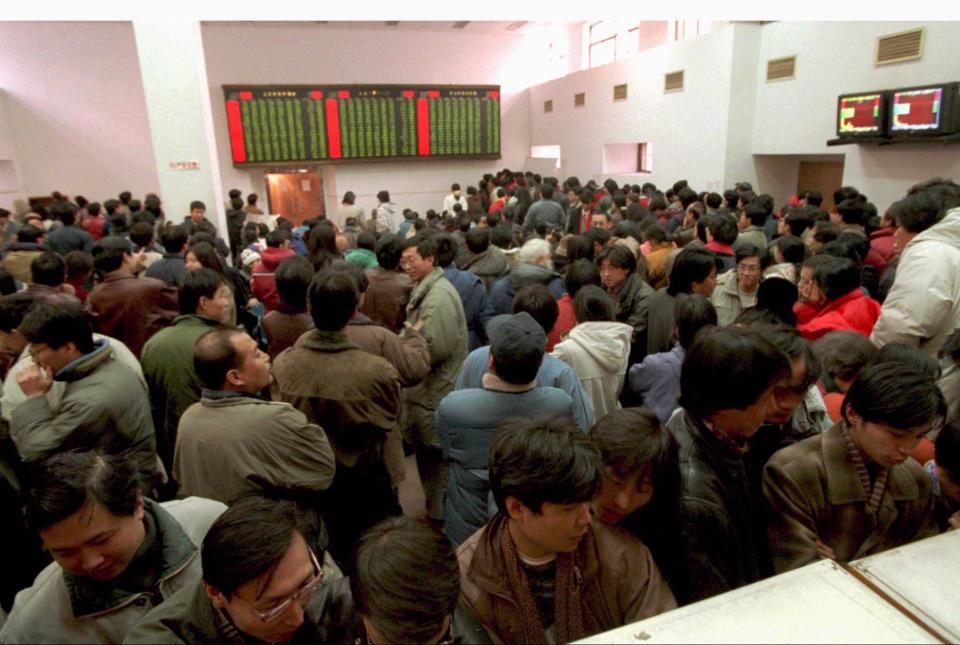

Retail investors and stock punters thronged the trading hall of a brokerage firm in western Beijing on December 16, 1996. Contrary to global convention, China’s stock market denotes losses in green and uses the red colour to represent gains and profits. Photo: Reuters alt=Retail investors and stock punters thronged the trading hall of a brokerage firm in western Beijing on December 16, 1996. Contrary to global convention, China’s stock market denotes losses in green and uses the red colour to represent gains and profits. Photo: Reuters>

Spurious purchases, driven by excessive speculation, have been the undoing of individual investors in China’s equity market. Some 92 per cent of them lost money in securities trading in 2022, according to a January 2023 survey by state-run broadcaster China Central Television or CCTV.

The hoopla once heightened fears of social disorder. Deng Xiaoping, the late paramount leader and architect of China’s capitalist reforms, soothed the concerns of his comrades, telling them that the market could be closed if the experiment flopped.

Some bold residents got rich overnight from dabbling in the initial batch of eight stocks, which surged by more than 20 times within three years. But wild swings in prices also left many unlucky punters nursing steep losses.

Stock investors checked stock prices at a brokerage firm in Shanghai on June 5, 2007. Photo: AP alt=Stock investors checked stock prices at a brokerage firm in Shanghai on June 5, 2007. Photo: AP>

During a market rout of 2015, more than US$5 trillion of value was erased from mid-June to late August. This prompted Beijing to pump about 1.5 trillion yuan in rescue funds to support the market. China’ securities regulator has long been tasked with stabilising the key market indicators, to pre-empt any social unrest.

Blossoms Shanghai re-enacted several scenes from the early days of the market history. There is the rented ballroom in Astor House Hotel on the bund, where the stock exchange’s first trading floor was located. Also featured is the trading counter inside the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China outlet on Xikang Road.

For some of the early stock investors, the scenes are also a rude reminder that years of hard-earned savings could evaporate within minutes of trading.

The street scene of Huanghe Road in Shanghai on January 10, 2024. Photo: Xinhua alt=The street scene of Huanghe Road in Shanghai on January 10, 2024. Photo: Xinhua>

“Traders at that time were so naive that they believed all the stocks were safe bets, guaranteed to eventually produce handsome returns,” said Jiang Guangyuan, a Shanghai native who has been dabbling in the market since its inception. “I suffered heavy losses in the 1990s because I was aggressive [in chasing returns], unaware of the risks and basics of the market.”

The latest episode or drama, playing out real-time before the global audience this week, is a wake-up call for policymakers in Beijing, said Andy Rothman, a strategist at Pennsylvania-based money manager Matthews International.

“Confidence among entrepreneurs and households has been shaken by poorly explained and poorly implemented economic and regulatory policies,” said Rothman, who previously served as a junior US diplomat in China. “Confidence can be restored if Beijing takes steps that demonstrate it is creating a clear and stable policy environment which supports the private sector.”

This article originally appeared in the South China Morning Post (SCMP), the most authoritative voice reporting on China and Asia for more than a century. For more SCMP stories, please explore the SCMP app or visit the SCMP’s Facebook and Twitter pages. Copyright © 2024 South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

Copyright (c) 2024. South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.