Human growth hormone shots from cadavers linked to Alzheimer’s, study finds

Five patients in the United Kingdom have developed Alzheimer’s disease that appears to be the result of contaminated injections they received as children decades ago, according to a new study that could change the way scientists think about the causes of dementia — and cause anxiety in patients who underwent the same therapy.

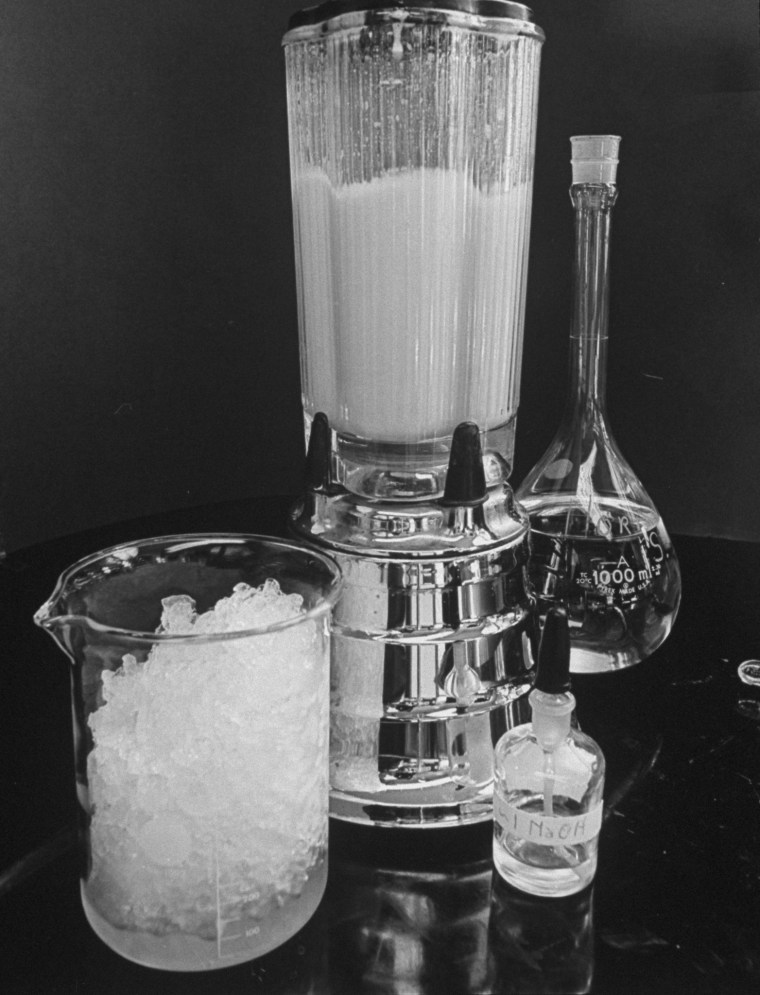

All five patients received injections of human growth hormone from cadavers for several years as a treatment for very short stature, according to the study, which was published Monday in the journal Nature Medicine. Scientists extracted the hormone from the cadavers’ pituitary glands, located at the base of the brain.

What the scientists didn’t realize at the time, however, was that in some cases, another substance was extracted as well, contaminating the batches: amyloid-beta protein. This protein is involved in the formation of the hallmark brain plaques seen in Alzheimer’s. Researchers said they can’t fully explain how being exposed to these proteins could trigger the creation of plaques and tangles in the brain that cause Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s cases are generally divided into two main groups: cases caused by genetic mutations and those that develop sporadically in the population in people over 65 due to a number of risk factors, such as smoking, obesity and high blood pressure.

The patients in the new study didn’t fit into those two groups. They developed dementia symptoms between ages 38 and 55. None had genetic mutations linked to early-onset dementia, the study found.

The study authors said their findings suggest a possible third way for Alzheimer’s to develop: through contaminated medical products.

Some doctors who regularly treat children for hormone-related issues and who were not involved with the research said they were surprised by the findings.

“This is new information that is not known by the medical community,” said Dr. Kupper Wintergerst, who chairs the American Academy of Pediatrics’ section on endocrinology.

Other doctors said they were concerned that a therapy once regarded as safe has caused so much harm.

“To hear that Alzheimer’s is linked to a medical treatment, that’s disturbing,” said Dr. Dennis Chia, an associate clinical professor of pediatric endocrinology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Christopher Weber, director of global science initiatives at the Alzheimer’s Association, noted that the study was very small. The findings would be more credible if other scientists get similar results in future studies.

Weber said there’s no risk to the general public.

“Alzheimer’s disease is not contagious,” said Weber, who was not involved in the new study. “You can’t catch Alzheimer’s by taking care of someone with Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s disease is not transmissible through the air, or by touching or being near someone with Alzheimer’s.”

Still, he said the study’s findings weren’t entirely new.

“We’ve known for a long time that it is possible to create abnormal amyloid buildup — similar to that seen in Alzheimer’s — in the brain of an animal by injecting it with amyloid-beta,” Weber said. “We also transfer human Alzheimer’s genes into animals to initiate abnormal, Alzheimer’s-like processes in their brains.”

Cadaver-derived growth hormone was given to 27,000 children worldwide from 1959 to 1985, according to the new study, including about 7,700 patients in the United States. Doctors used hormones taken from cadavers before a synthetic version became available.

It’s possible that other patients who received cadaver-derived hormones are at higher risk of Alzheimer’s, the study authors said. But they added that they don’t expect to see a huge wave of cases.

“The actual risk of transmission of Alzheimer’s disease in this context is really very low and these are probably going to be very rare cases,” lead study author Dr. John Collinge, a neurologist and the director of the University College London Institute of Prion Diseases, said at a news briefing Thursday.

Collinge said patients should be aware of the potential risk for Alzheimer’s and, if needed, seek out testing and treatment.

“It’s possible that if we catch people at an early stage” of Alzheimer’s, he said, “they may be more amenable to treatments that are becoming available.”

Children being treated for short stature today are not at risk, because doctors have used synthetic growth hormone since 1985.

“I don’t think people should be alarmed,” said Dr. Paul Kaplowitz, a professor emeritus at Children’s National Hospital who specialized in pediatric growth disorders.

Read More: Human growth hormone shots from cadavers linked to Alzheimer’s, study finds