The Earth’s tectonic plates made the Himalayas — and could rip them apart

In the heart of Asia, deep underground, two huge tectonic plates are crashing into each other — a violent but slow-motion bout of geological bumper cars that over time has sculpted the soaring Himalayan mountains. But the ongoing tectonic collision that formed the highest mountains in the world may also be cleaving Tibet in two, according to new research.

A team of scientists in China and the United States studied seismic waves underground from earthquakes that struck in and around Tibet and analyzed the geochemical makeup of gases in hot springs at the surface. They found that the Indian plate may be behaving in surprising ways as it smashes into the Eurasian plate.

The findings have not yet been peer-reviewed, but a preprint version of the study was posted online and the researchers presented their work in December at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Scientists have known that the collision of the two tectonic plates, which began roughly 60 million years ago, caused the edge of the Eurasian plate to buckle, bulging and twisting into what we now recognize as the Himalayas. But precisely what is happening underground as the Indian plate continues its charge has been something of a mystery.

Some experts have suggested that as the Indian plate is subducting, the technical term for being forced under the Eurasian plate, it is pushing horizontally beneath Tibet, while others think the Indian plate is diving deep underground in a more vertical fashion.

The new study suggests that the Indian plate is plunging under the Eurasian plate, but as that process plays out, part of it is splitting apart under Tibet, with the eastern half of the slab tearing away from the western portion.

“We speculate that this slab tear may divide the mountain chain along its length,” the researchers wrote in a summary of their findings.

As the plate cleaves in two below ground, it could open up the region to earthquakes and other hazards, the scientists said.

Barbara Romanowicz, a professor in the department of Earth and planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved with the study, said the findings offer an interesting — and plausible — explanation for what is happening in a very dynamic part of the world.

What’s more, the study hints at the potential implications if the Indian plate is splitting in two.

“If you have a tear like this, it’s a zone of weakness,” she said. “So you might expect that it could be the location of some large earthquake to accommodate the whole motion of the Indian plate under the Eurasian plate.”

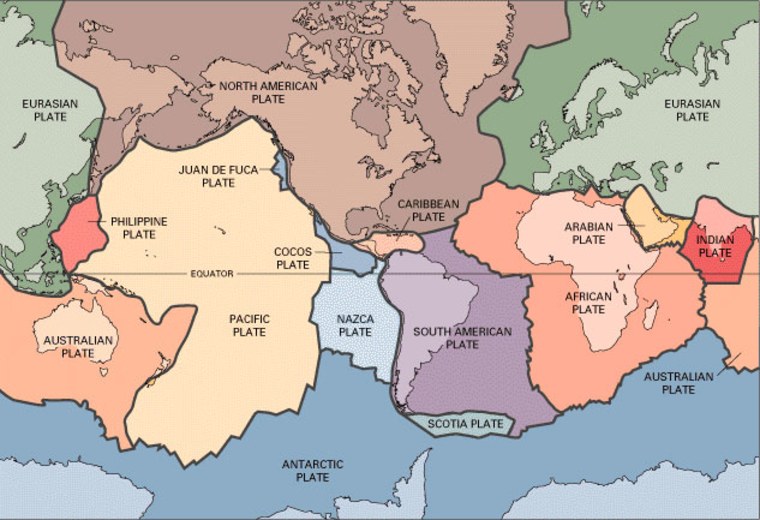

Tectonic plates are made up of Earth’s crust and the rigid top layer of the mantle, known as the lithospheric mantle. The planet has around a dozen large and irregularly shaped tectonic plates that constantly smash into, push atop, slide under or stretch apart from one another.

“The crust and the rigid part of the mantle should all move together, but this paper is arguing that the lithospheric mantle is peeling away, leaving the crust behind,” said Zach Eilon, an associate professor of geophysics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who was not involved with the study. “That’s interesting and, in some ways, is actually a little controversial.”

The reason for the potential controversy is because there is no consensus yet within the scientific community on how the collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates is playing out — or what it means for the planet.

“Everybody has something to say,” said Joshua Garber, an assistant research professor in the department of geosciences at Pennsylvania State University, who did not take part in the study. “This area is almost like a golden calf, or the Holy Grail, for geologists. There are lots of people trying to understand what’s going on because it’s so unique.”

The region’s special status owes to the fact that it is the only place where a continental plate collision is occurring in real time. These chaotic pileups have happened many times in Earth’s history, including 350 million to 400 million years ago in a process that created the Appalachian Mountains, but modern examples are very few and far between.

“We have a very limited natural laboratory,” Eilon said. “It’s a vanishingly short snapshot in time that Earth has provided for us during our puny lifetimes, so this is kind of the only game in town for studying this specific process of continental collisions. And that’s pretty phenomenal.”

Read More: The Earth’s tectonic plates made the Himalayas — and could rip them apart